2020 Winner

Book Award Years

Finalists

In Iman Al Barghouti's bedroom, she hangs the suit her husband, Nael Al Barghouti, who is the longest-serving prisoner in Israeli custody, having spent 41 years in prison. Nael was arrested on April 4, 1978 after carrying out a commando operation in which one Israeli was killed. Released during Shalit’s agreement between Hamas and Israel in 2011, he has been arrested again and sentenced to life imprisonment. Photo: Antonio Faccilongo/Reportage by Getty

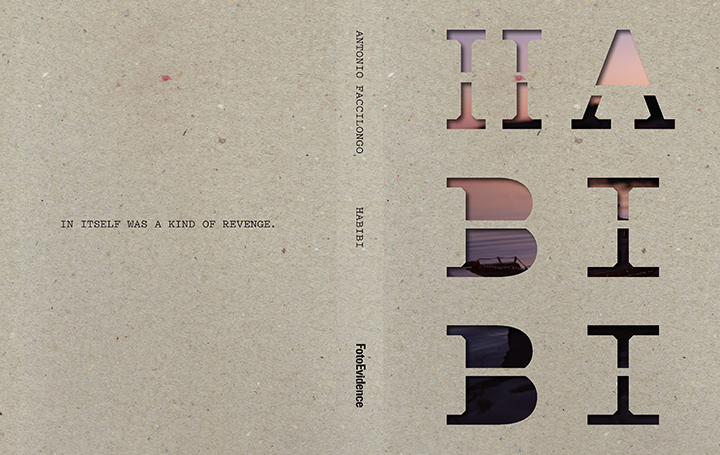

HABIBI

by Antonio Faccilongo

Recipient of the 2020 FotoEvidence Book Award with World Press Photo

Cover design: Ramon Pez

The book Habibi is a chronicle of a love story set in one of the longest and most complicated contemporary conflicts, the Israeli-Palestinian war. In 2008 I went to Palestine for the first time. As my plane landed at Tel Aviv airport, the bombing of the war began, later to be called "Operation Cast Lead,” the first after the second Intifada. A bloody 22-day lightening war in which more than 1,300 people died. The violence I witnessed in those days deeply affected me. From that moment on, I felt the need to tell the realities hidden behind the conflict that best make us understand the meaning of living in that place, and at the same time restore dignity to the people who live there.

After I got home, I continued to follow the developments of the conflict and found that a very large number of men in the Palestinian refugee camps had been arrested. I have asked myself several times what the absence of these men within this community meant and what consequences it could have on the balance of families who already live in a contested territory. So I went back to Palestine to meet them and tell some stories of their daily life, their experiences and their feelings.

The story that most affected me emotionally is the one told in Habibi. In 2014, one of the prisoners' wives managed to give birth to a baby boy without having met her husband, who was serving a life sentence in an Israeli prison. This is the Holy Land and virgin birth isn’t unheard of but not for a couple of thousand years. Today, this is possible thanks to in-vitro fertilization. The determination of the first women who did in vitro fertilization was an inspiration for many other wives, who subsequently followed the same path. The power of life that goes beyond everything, challenging evidence and rationality. I was thrilled to see their strength. Alone, they bravely faced the difficulties of life in a hostile territory, keeping alive the presence of men in their homes and hearts, taking care of the family with the hope of reuniting with their husband.

One of the most significant experiences I have had in making this work was sharing the exhausting journeys to reach the prisons on the day the wives visit their husbands. On one of these trips I met Lydia Rimawi together with her son Majd. I will never forget Lydia's consoling embrace on the bus. A hug full of love but also of strength and protection, of a proud woman who faces life with pride. I was touched by that gesture, delicate and strong at the same time, and by everything it meant for her, as for all the other women, who find themselves in having to raise their children alone. It was at this juncture that I felt the need to meet the detainees and understand the reasons that led them to perform those acts that keep them away from the affection of their loved ones. They are excluded from life and live with uncertainty for the future. I have tried several times to obtain a permit to visit them, together with their families or even alone. I applied, officially and with informal inquries, not only to take pictures but also to be able to talk to them and hear their reasons with my own ears. Unfortunately, this possibility has always been denied me. The official response was that only Israeli media can obtain this type of permit. Their reply made me feel as though, as a foreigner, I was less worthy, an individual with fewer rights, an experience common in the occupied territories. But I also felt that denying me a permit was primarily designed to stop the prisoners from being heard by a wider audience.

The concrete barrier that separates these territories is only the emblem of this exclusion. Just as prisoners live behind bars, so their families live in the shadow of the wall. A very heavy wall that does not let the wind pass, that stifles hope. A separation that heavily effects the lives of both peoples and that certainly does not help dialogue and understanding.

In Gaza, I felt the sensation of being locked up in a context in which life seems impossible, in an environment that leads to being tired and exasperated. It sometimes seems impossible to smile and imagine a future there. An entire generation of children is growing up in with the daily agitation of an endless war and the complete disinterest of the international community. Faced with all this, I have asked myself, many times, if those born in these places have the same right to love as those born elsewhere. The women I have known in recent years have answered my question by showing me how sweetly and forcefully children can grow even in difficult environments like this. Love makes you see beyond obstacles and pushes you to overcome the limits of your existence. Love protects you in the face of difficulties. Love sums up everything these women do for their husbands, their children and their families.

(L) A prisoner-made cardboard boat floating in the Dead Sea. It is common among inmates to make handmade items to donate to their loved ones during family visits to prison. These small gestures of affection help prisoners and families to feel closer and overcome sadness and loneliness.

(R) Dead Sea, (Palestine), 11/25/2017.

Dweidar Awad (40) is the wife of Zuhair (50) who is a Palestinian prisoner detained in an Israeli jail. This is the first time that Dweidar has gone to the Dead Sea though living only 15 minutes from the sea. Her family is very poor and has never had the money to pay for the ticket to access the beach. Photos: Antonio Faccilongo/ Reportage by Getty

(L) Bethlehem (Palestine), 11/24/2017.

The dividing wall separating the Israeli highway from the Palestinian hills. This photo shows without judgment, the separation and the differences between two worlds constantly in contrast; the developed and technological world of Israel and the rural one of Palestine.

(R) Ramallah (Palestine), 11/27/2017.

Manwa Shaheen is the wife of Ahmad who was arrested in 2001 and sentenced to 22 years. They have a son Ali born through IVF. Manwa lost another child conceived through IVF. She would like to try again to do in vitro fertilization because she also wants to have a daughter. Photos: Antonio Faccilongo/ Reportage by Getty

(L) Tulkarem (Palestine), 01/25/2015.

A portrait of Atta Abdelgami (45), who is serving three life sentences. He is the husband of Rula Ali Ahmed Abdelgami (32). The couple have two children born through IVF. One of the reasons these prisoners are in jail is that they took part in military actions. It is common to find portraits of this kind in their homes, as they have the function of making their loved ones feel closer and, because they are viewed as martyrs, bringing the new generations closer to the resistance.

(M) Bethlehem (Palestine), 07/30/2015.

A pen tube containing sperm is hidden in a chocolate. This photo shows the best known method, also by Israeli police, used for the smuggling of sperm. While kept physically separated from visiting spouses and adults, inmates can play with their children for ten minutes at the end of each session. During these short visitations, some of the men pass the snacks to their children, practicing one of the methods used to smuggle their seminal fluid out of prison to conceive children through in vitro fertilization. The sperm is only viable for up to 12 hours.

Thanks to the relationships established following this story, I was able to take this picture between the prison and the fertility clinic.

(R) Jericho (Palestine), 01/10/2011.

A portrait of a Palestinian woman, who works for the Prisoner's club, waving a Palestinian flag. The Prisoner's club is a non-governmental organization that supports Palestinian political prisoners and their families. Photos: Antonio Faccilongo/ Reportage by Getty

(L) Beit Rima (Palestine), 20/12/2018.

Lydia Rimawi (39) lying on her sofa. Her son Majd, who is resting on a couch behind her, was conceived through IVF. Lydia’s husband, Abdel Karim (45) has been under arrested since June, 2001 and sentenced to 25 years for involvement in the 2001 murder of Israeli Tourism Minister Rehavam Zeevi.

(M) Gaza city (Palestine), 01/18/2015.

A newborn, born few hours earlier, in an incubator at Gaza's Al-Shifa Hospital.

(R)Tulkarem (Palestine), 01/25/2015.

Amma Elian (40) is the wife of Anwar (40). He was arrested in 2003 and sentenced to life imprisonment. She holds her twins. In vitro fertilization raises the chances of having a multiple birth. About one in six IVF pregnancies result in a multiple a birth. This is very high compared to the natural conception of twins, which is about 1 in 80 births.

Initially, Palestinian women and their families were afraid to declare that they had carried out in vitro fertilization because they could not know the consequences of their choice. At that time religious authorities in Palestine had not clarified their position on IVF. The procedure is now accepted in specific circumstances. In April 2013, the Palestinian Supreme Fatwa Council issued a religious fatwa that detailed the restrictions: limiting the process to those men with a long sentence, a marriage consummated before imprisonment, and no other way for pregnancy. The husband and wife also need to fill out paperwork, and families are expected to provide multiple witnesses confirming that the sperm sample belongs to the man. As a result, a greater degree of openness now exists for those who have had children in this manner. Photos: Antonio Faccilongo/ Reportage by Getty

Saffa (Palestine), 11/26/2017.

At the day for visiting the prison, families of Palestinian prisoners wait at the Israeli checkpoint for their documents and special permits to be inspected. Photo: Antonio Faccilongo/ Reportage by Getty