2016 Winner

Book Award Years

In the 1840s, the Canadian government created the Indian Residential School system. This network of Church run boarding schools forcibly assimilated indigenous children into Western Canadian culture.

Attendance was mandatory, and Indian Agents would regularly visit reserves to take children as young as two or three from their communities. Many of them wouldn’t see their families again for the next decade.

Students were punished for speaking their native languages or observing any indigenous traditions, routinely physically and sexually assaulted, and in some extreme instances subjected to medical experimentation and sterilization.

The last residential school didn't close until 1996. The Canadian government issued its first formal apology in 2008.

The lasting impact on Canada's indigenous population is immeasurable and grotesque. At least 6,000 children died while in the system — so many that it was common for residential schools to have their own cemeteries. And those who did survive, deprived of their families and their own cultural identities, became part of a series of lost generations. Languages died out, sacred ceremonies were criminalized and suppressed. The Canadian government has officially termed the residential school system a cultural genocide.

Signs of Your Identity will be a photo book, a collection of interviews and first-person accounts, and most importantly, a teaching tool. These multiple exposure portraits document survivors who are still fighting to overcome the memories of their residential school experiences, reflected in the sites where those schools once stood, in the government documents that enforced strategic assimilation, in the places where today, First Nations people now struggle to access services that should be available to all Canadians.

These are the echoes of trauma that remain even as the healing process begins.

This is Mike Pinay, who attended the Qu'Appelle Indian Residential School from 1953-1963. "It was the worst ten years of my life. I was away from my family from the age of 6 to 16. How do you learn about relationships, how do you learn about family? I didn't know what love was. We weren't even known by names back then, I was a number." "Do you remember your number?" "73."

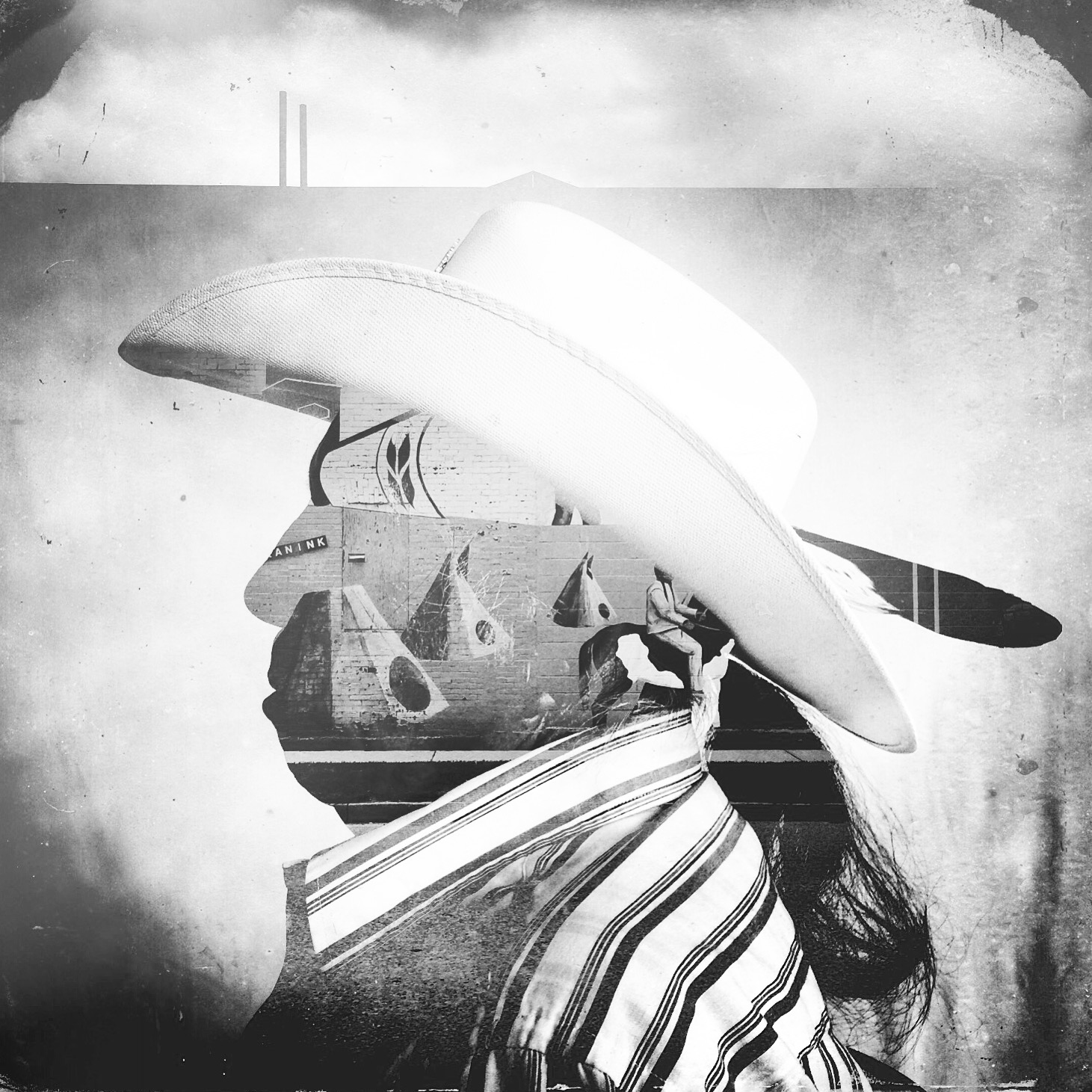

This is Jaime Rockthunder, who went to the Qu'Appelle Indian Residential School from 1990-1994. She was sexually assaulted during her time there, and her younger brother was raped by a classmate. Jaime said, "He finally told me about it, almost 20 years later, and he blamed me. All he could say is, 'Why didn't you protect me?'" One of the most haunting legacies of the residential school system is how much of the trauma transitioned into lateral violence — entire generations of indigenous children grew up without their families and frequently were subjected to unspeakable physical and sexual violence. That anger and hurt was often channelled into lashing out at each other, and, when they eventually had children of their own, the next generation as well.

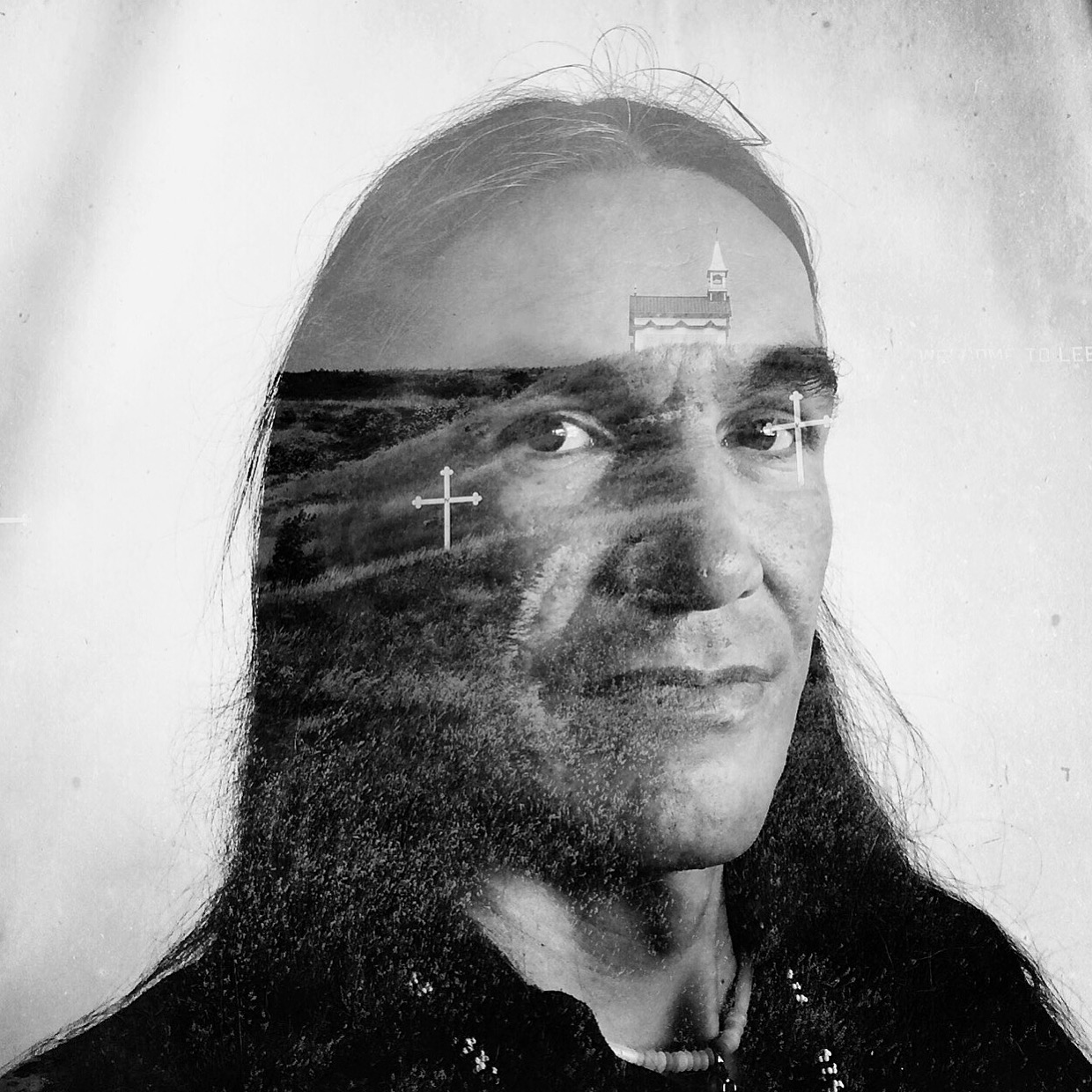

This is Valerie Ewenin, who went to Muskowekwan Indian Residential School from 1965-1971. "I was brought up believing in the nature ways, burning sweetgrass, speaking Cree. And then I went to residential school and all that was taken away from me. And then later on I forgot it, too, and that was even worse." Throughout Canada, it was standard procedure for the teachers, priests, nuns, and administrators who ran residential schools to punish students for speaking their own languages or trying to practice their own faith. For indigenous children who were taken away from their families as young as 3 or 4 and sometimes wouldn't get to see their families again for as long as a decade, that meant a complete forced disassociation from their own cultures and identities. Imagine finally getting home to your reserve as a 14-year-old and realizing you can't communicate with your parents anymore because they only speak Dene and you only speak English. That happened to thousands and thousands of First Nations children.

This is Marcel Ellery, who went to Marieval Indian Residential School from 1987-1990. "I ran away 27 times. But the RCMP always found us eventually. When I got out, I turned to booze because of the abuse. I drank to suppress what had happened to me, to deal with my anger, to deal with my pain, to forget. Ending up in jail was easy, because I'd already been there."

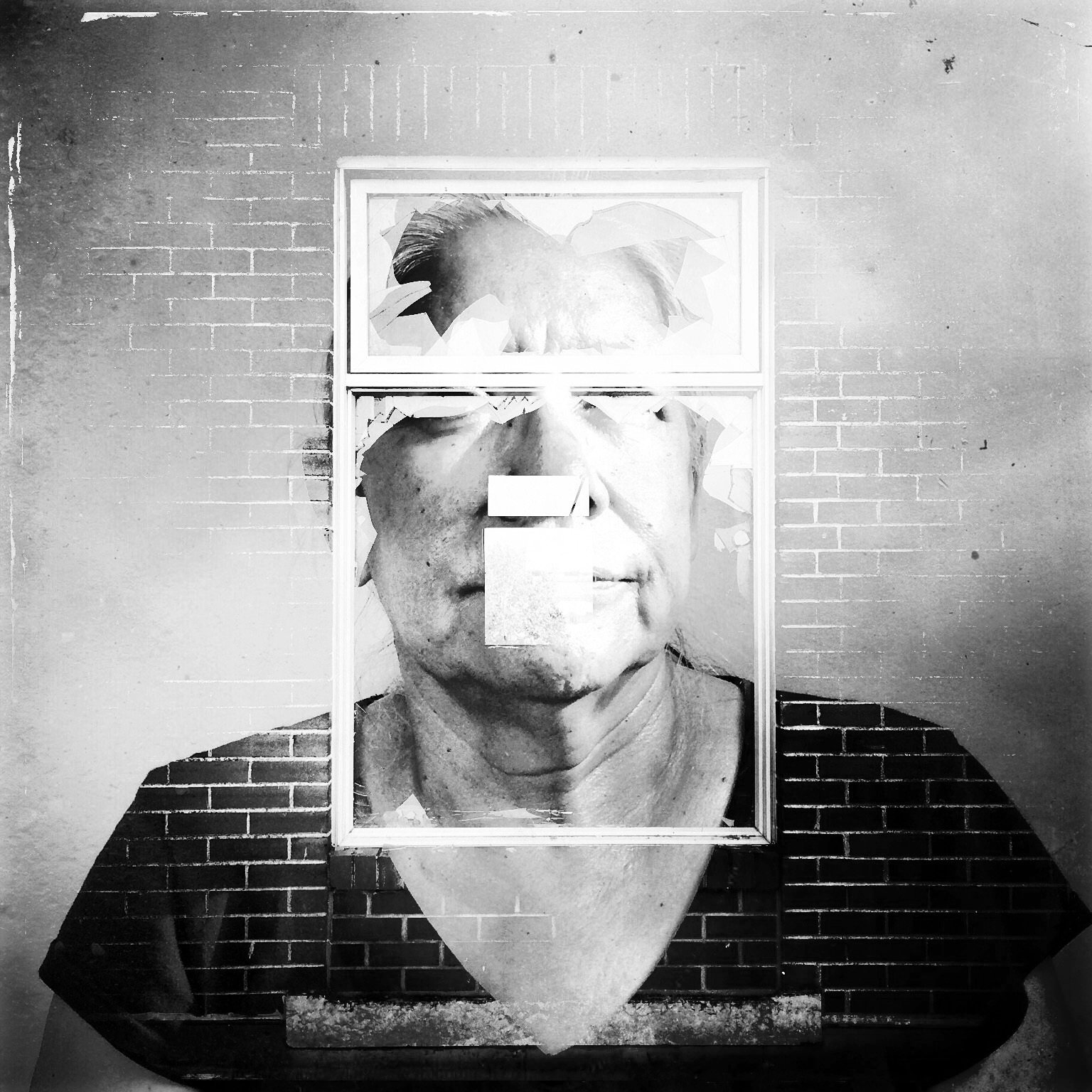

This is Gary Edwards. He attended three residential schools in Saskatchewan between 1970-1978. He remembers that routinely, after mass, the priest and two assistants would lock the church doors, don gas masks (the old-fashioned canister kind), and open clear, seemingly empty mason jars. Minutes later, some students would begin to vomit, or seize, or to develop severe nosebleeds. To this day, he has not been able to figure out what was happening during those weekly sessions, but he believes that someone was using him and his schoolmates to test nerve gas. While that's hard to prove, for now, there are many documented cases of medical testing and forced sterilization of indigenous children while they were at residential school.

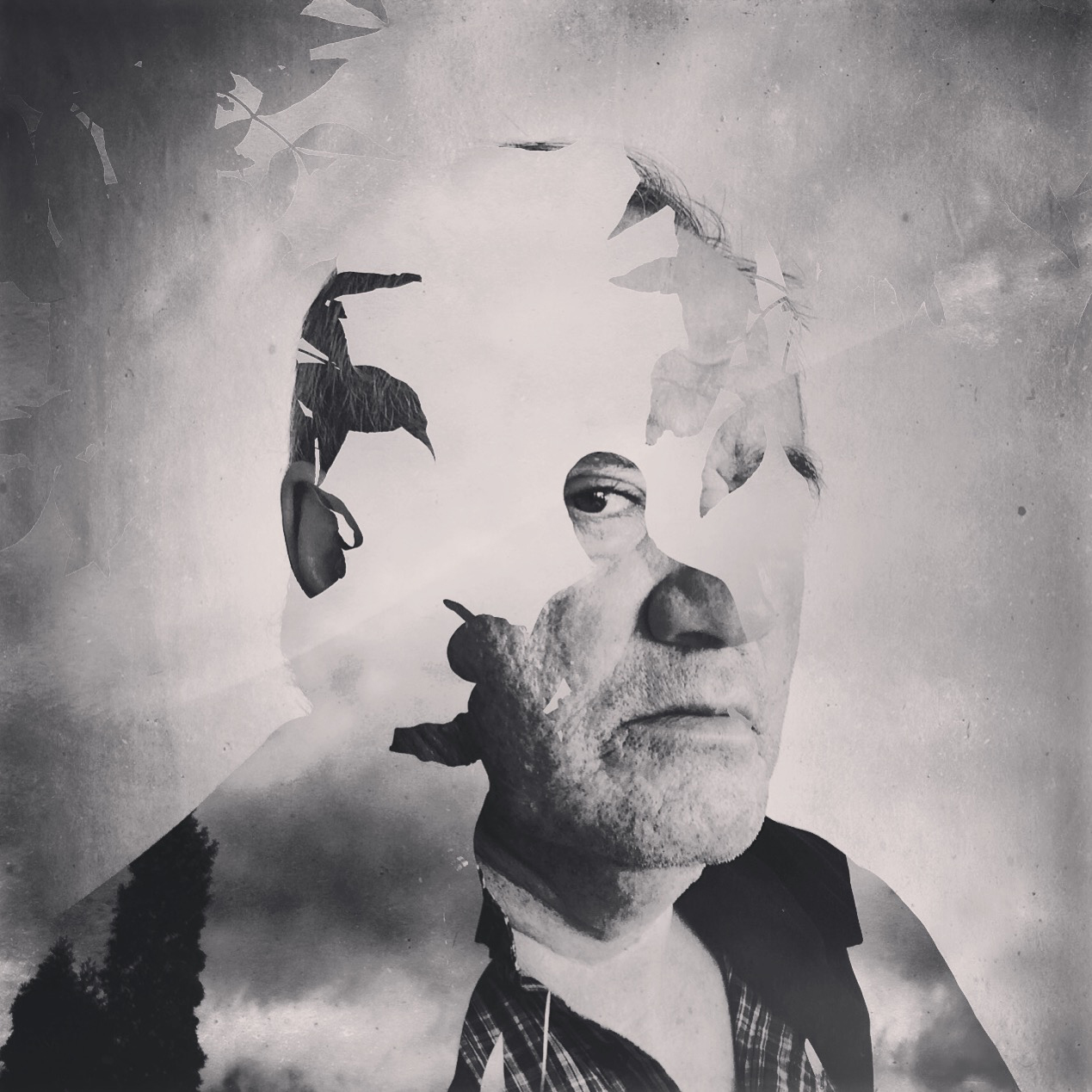

This is Grant Severight, who went to St. Phillips Indian Residential School in Kamsack, Saskatchewan from 1955-1964. He has spent decades working as a counsellor, helping other residential school survivors cope with their experiences. While the physical and sexual abuse that almost every indigenous child encountered is often the focus of the residential school experience, it's important to note that the act of forced assimilation is just as sinister and psychologically damaging. Students were punished if they spoke their native languages or tried to practice any indigenous customs. Their hair was cut, their clothes were taken away. At best, little children saw their parents two months of the year. At worst, they wouldn't see their families for a decade. The government-commissioned Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded a seven year-long study in June, and deemed the schools a tool of cultural genocide. Grant said, "We as a people have normalized every conceivable dysfunction that we experienced in residential school. Negativity is transmitted — and if we don't deal with it we pass it on. Even in school, kids who themselves were terrorized grew up to be abusers. We need to figure out how to heal from that."

This is Rick Pelletier, who attended the Qu'Appelle Indian Residential School from 1965-1966. He was 7 years old. He was being beaten so badly -- both by the nuns and by older students who themselves had been subjected to extreme physical violence -- that when his parents went to take him back for his second year, he ran away. Later, his parents enrolled him at a local public school in Regina, but the experience was just as bad. Being one of the only First Nations students at school meant he was the object of bullying and racism. "I still don't know which was worse."

This is Angela Rose, who went to Gordon Indian Residential School from 1980-1986. "I used to be able to speak my language when I was little. But now, because of residential school, I only know how to say hello and count to ten. I turn on the native radio station and I just like to sit and listen. I can't understand what they're saying, but every once in a while a word will pop out at me and it'll jog some small memory. I've lost a lot of things, but I think that's one of the ones I miss most."

This is Jimmy Kevin Sayer, who went to Muskowekwan Indian Residential School from 1983-1984. Like so many others, he was sexually abused while a student. Both of his parents also went to Musekowekwan as children, and struggled with alcoholism throughout their adult lives. According to Jimmy, "I've spent half my life incarcerated, and I blame residential school for that. But I also know I have to give up my hate because I'm responsible for myself. I have three adult daughters and I was in jail for the duration of their childhoods — I have a 2 year old son now and I need to be there for him. I have to be different."